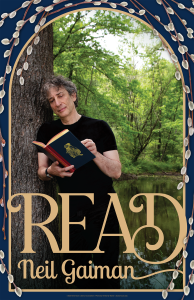

Neil Gaiman wears many hats: novelist, journalist, comic book writer, screenwriter, television producer, musician. And he’s a fierce supporter of libraries. The author of American Gods, Neverwhere, Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch, The Sandman, Coraline, and many more has had a lifelong love affair with reading-he’s even featured on a brand-new Celebrity READ poster from ALA Graphics-and he credits librarians for fostering his curiosity about books and learning at a young age.

Gaiman spoke with I Love Libraries recently about the importance of libraries, comic books, book banning in the U.S., movies, and more.

What drew you to sci-fi and fantasy as a young reader?

I have absolutely no idea. When I was a kid, I loved books. Books of all kinds. I remember there wasn’t necessarily a feeling of being drawn to fantasy as there was an absolute love of everything that I had read so far.

You know, you start out reading, and you’re reading books about mermaids; you’re reading Snow White; you’re reading about the Pied Piper of Hamelin and so forth. You read The Wind in the Willows. You read Alice in Wonderland. And you want more of whatever that is, that feeling of wonder, that feeling of escape, that feeling of being able to get away from this world and visit others.

Were comic books a part of that world?

Comic books turned up. I liked my British comic books. They were sweet. But then they started reprinting Marvel comics, and they were reprinting them from the beginning, which was fabulous even though they were in black and white. I was encountering Thor, the X-Men, the Hulk, Spider-Man, all these characters from the beginning which was a lovely way to get to know a universe of characters.

And then when I was about 7, my father-for reasons that I never found out-suddenly had a huge box of Marvel and D.C. comics, a box of American comics. And I was lost. I remember all of them. I remember the covers. Amazing color stories. And I fell in love with superheroes. I just thought they were the best things in the world.

When I got a little bit older, and by a little bit older I mean 10 years old, I got less interested in superheroes and more interested in the creepy stuff. Superheroes felt a little bit predictable to me in the sense that, you know, at the end of the day, it was “somebody hits somebody and the good guy eventually wins.” Whereas I liked creepier stuff because I never really knew who was going to win; I never knew quite what was going to happen next. So I would go to comics like The Phantom Stranger and Swamp Thing and House of Mystery and House of Secrets. They were my happy place.

You’ve mentioned that it was discovering Alan Moore’s revitalization of Swamp Thing that led you to want to write comic books.

I loved the original Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson’s Swamp Thing. When I was 11 or 12, I thought they were the best comics in the world and I loved going back to them. So, when I saw in 1983 that somebody was writing a Swamp Thing comic, I was very unimpressed. I hadn’t read comics for five or six years at that point. I was in Victoria Station [in London], and I picked one up and read it in WHSmith. It was really quite good, but I put it back because I didn’t buy comics anymore. I did this for about two or three months, and then gave in and bought my first Alan Moore-The Saga of the Swamp Thing-and just fell. At that point I was an Alan Moore fan. I thought he was the smartest person.

Literally, I’m like, “Okay, I’m a book reviewer. I’m a film reviewer, and what Alan is doing right now in comics-he’s as interesting and as deep as anything that anybody is doing in books or on television. And that’s so amazing.”

It was huge for me. I wrote to Alan, and when my first book came out, I sent him a copy. And he phoned back, and we became friends. The first time I met him, I said, “Will you show me how to write comics. I want to know; I don’t actually understand.”

I recently saw two videos of you on Instagram that I loved. The first featured you at Waxworks Records ecstatically pressing a vinyl album of the soundtrack for the Netflix adaptation The Sandman. And the second was a clip of you backstage at the play adaptation of your book The Wolves and the Walls. Those videos got me thinking about the life of a work after it leaves a writer. Your books have been adapted into many mediums: film, television, theater, and more. Are you ever concerned about your work being in someone else’s hands and the final product not being in line with your original vision?

I tend to be Darwinian in that the good things work, and the ones that are really good last. They find their audience, and they last. And, you know, I would rather say yes to somebody who’s enthusiastic and seems to have a calling than say no.

With Stardust, that was fun because [director] Matthew Vaughn got to make his film. With Coraline, that was fun, and I got the sense that once it was done, it was like, “Oh, we just made something that will be around forever.” I love the fact that it’s now 12, 13, 14 years after Coraline the movie was released, and it just goes on and lives. It has this amazing life as a movie. So I would always much rather say yes to things and see what magic they make or they don’t make.

You’re an author of many books that have been challenged and banned throughout the years. What does it feel like to experience that?

On one hand, you feel like it’s an honor, and on the other hand, you feel anger and revulsion. And both of those things are true. I am honored to be a banned book whenever it happens, because I look at the history of books that have been banned; the history of who bans them. I will never be on the side of the people who ban the books. I’m on the other side. I will always be on the side of the libraries.

As far as I’m concerned, if you really can’t figure out which political party or which politician to vote for, just ask if they’re on the side of libraries. Are they voting to fund their libraries? Are they voting to keep them free? Then vote for those guys. They’re probably the good guys. And by the same token, the book burners, the book banners, they’re probably the bad guys. It’s a good way to bet.

But it also makes me tremendously angry. Because for a lot of people, libraries are still the way that they can get books, the way that they can afford books, the way that they can access books. And when you challenge a book, when you take it out of a library, when you do what some people have done…. There was a case a few years ago where some library workers decided that some books were Satanic, I think it was The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. So they conspired to always keep the books checked out, which was fine, because it didn’t quite get discovered. But when they decided to actually burn the books, then they got far mad. And that kind of thing, it’s just like, somebody would have liked to read that. You don’t have to do that. They’re not making the world a better place by taking ideas out of it.

Why do you think we’re seeing such an increase in book bans and challenges now? What do you think they’re afraid of?

I don’t actually think they’re afraid of anything. I think they feel that it’s a way to exert power, and it’s a way to exert control, and it’s a way to show that they’re in charge. The scariest thing is that, in books and movies, all too often the bad guys are the ones going, “Ha ha, I am a bad guy. I have an evil plan.” But all too often when you start digging into history, the real bad guys are the ones who are going on about doing the “right thing.” It’s absolutely the right thing to murder six million Jews. It’s absolutely the right thing to invade Africa. It’s the right thing to do to cut off these people’s hands or whatever. And that, unfortunately, is where the most monstrous things happen.

What do you think that we as book lovers, librarians, parents, teachers can do to combat this?

I think the most important thing right now for us and for everybody is to get involved locally. People don’t necessarily stand for their library boards; they don’t stand for their school boards. It’s work, and we’re all busy. That means the people who do stand for library boards and who do stand for school boards very often get onto the boards at their local libraries. That can be good when they are people of good will.

I spent this morning being shown around the building that is going to become the new Woodstock (N.Y.) town library. And it’s going to become this amazing community hub. I walked out so enthusiastic at the idea of this place that will be the dream of a library. It’ll be amazing. I love the fact that the library board is behind it. They’re supporting it, and they support their librarians. I’m looking forward to being a part of this.

But I’m very aware that there are a lot of towns where the goal of the people who have been elected to their library board is to close down the library-or at least stop people from getting access to things they don’t want them to have access to. That can be knowledge, that can be the idea that the things people do outside of their town can be the right way to do things or at least that there is another way of doing things. It always comes back to think globally but act locally.

You credit librarians with fostering your lifelong love of reading. Do you have a favorite library story, past or present, that you can share?

I get told not to tell this by librarians, because librarians are terrified that people will view them as cheap childcare. But when I was from, I think the age of 7 onwards, my parents would drive me to the local library in the morning [during the summer], which is where I wanted to be during my school hours. And I would just sit there going through the card file. It had an old-fashioned card file. And I would go through the card file looking for words like witches, robots, outer space, ghosts, monsters, giants, magic, anything like that. And I would read everything I could in those categories. And I’d read anything that looked interesting. And after a while, I gave up and just started reading through alphabetically.

By the end, I had read the children’s library, and I loved it. And I would have been about 11 or 12 when I went, “Now, I can start on the adult library.” And I went out and tried doing that alphabetically and failed within, like, four books. It was just, “I hate these books.” So I became much pickier when I moved into the adult library.

But I remember the joy of being able to talk to the librarian about things I wanted to read that they did not have. I remember them ordering for me the complete plays of W.S. Gilbert, which I wanted to read. When the copy came in, I got so excited. It was an interlibrary loan. I remember sitting there trying to figure out with the librarian who the authors of The Three Investigators books were, so they could order some more. It was Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators. I was like, “Okay, I need Alfred Hitchcock. Who is the author?!” We can’t figure it out. And, you know, I’m a 9-year-old, and this is a grown-up librarian, and we’re working together. I think the “working together” is the most important thing.

The library was a space where I could go as a 7-year-old, as an 8-year-old, where I was treated with respect. I was treated as one of the people who was there. I could talk to the librarians. And I did. Most of the time they’d just ignore me-I’d be sitting reading my book, and I was the happiest kid that could be in the corner reading-but when I did interact with them, they interacted with me as a customer, as a patron, as somebody who was entitled to be there, deserved to be there, had every right to be in that space. And I still remember that because nobody did that. That’s not a thing that happens when you’re 7 years old, but it happened to me.

You’re on a new Celebrity READ poster holding Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. Why did you choose this book?

You’re on a new Celebrity READ poster holding Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. Why did you choose this book?

I wanted a book that I could link everything, from being a kid to now. It was a book that I love wholeheartedly now and loved then. The Wind in the Willows is a masterwork. It’s beautifully written. It’s beautifully thought out. It contains magic on a level that I find fascinating because-apart from the fact that you have animals who are both animal-sized and somehow human-sized doing things that human beings do-there is nothing fantastical about it. And yet, in the middle of the book, in a chapter called “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”-which often gets omitted now, which makes me sad-the great god Pan shows up. And Pan is there for the animals as kind of a nature god who’s rescued a lost baby otter. If there was ever a chapter in a book that sort of puts you in touch with the luminous, it’s that chapter.

I remember my first ever encounter with the story as a 3-year-old kid in Portsmouth, down in Southsea, in Hampshire, England, watching actors wearing costumes-a toad costume, a rat costume, a mole, and a badger costume-and just marveling at the magic of it. And then discovering the book and going, “I’m reading an important book. I’m reading something that I’m learning from.”

I look back at it now and think, “You’re an almost perfect book.” The only place that it feels less than perfect to me now is that there’s really only one female character. But she comes in and does one of the most important things that any of the characters do, so that’s alright.

One last question. It’s a two-parter: What are you reading now, and what was the last movie you watched?

I’m reading The Curator by Owen King, and I’m loving it. It’s a beautiful book. It reminds me a little bit of Winter’s Tale by Mark Helprin. One of those books that straddles fantastic and modernist literature in that it seems to be set in our world, seems to be set maybe 100 years ago. Yet it’s in a city that has never existed or a country that has never existed. And it’s as magical as it is political and beautifully crafted.

The last movie I watched was on the plane home two days ago. I watched The Lady Eve, the Preston Sturges film. The last movie I saw in a movie theater was Elemental, the Pixar film, which I saw with my son, and we loved it. It’s a lovely film about being an immigrant in many ways. And they managed to do that thing that good fantasy does, which is we see ourselves through a mirror reflected at 45 degrees. And we can see ourselves much more clearly for not being right up against it but having a little bit of distance.