Jason Reynolds is one of the most acclaimed writers of young adult literature in the world. The recipient of a Newbery Honor, a Printz Honor, an NAACP Image Award, and multiple Coretta Scott King honors, Reynolds is the bestselling author of Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks, All American Boys (with Brendan Kiely), Long Way Down, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You (with Ibram X. Kendi), Stuntboy, in the Meantime, Stuntboy, In-Between Time, and Ain’t Burned All the Bright, as well as books in the Mile Morales Spider-Man franchise for Marvel Entertainment. And he has great taste in music.

Reynolds spoke with I Love Libraries recently about writing for young readers, the fun and challenges of working in the superhero world, book bans, library memories, music, his new ALA Celebrity READ poster, and more.

What led you to write for younger readers? When you start a new work, do you set out with a young audience in mind?

These days, yeah, but that’s not the way it started. When I sit down these days I’m thinking about the audience, for sure, because I think it’s necessary. I know it’s sort of a writer taboo; it’s a faux pas for writers to think about the audience-or so I’ve heard from many of my colleagues-but I think when you’re writing for young people and you’re not a young person, it would behoove you to at least consider them, you know?

But it started a long time ago. When I got into this industry, I was 21 years old and I had written what I thought was an adult book. Me and my buddy Jason Griffin had written what we considered to be adult books, because when you’re 21, you obviously feel like you’re 41. And you believe that the tone of your work and your life for that matter is far more advanced and mature than it might be. So, when I turned this book in, they categorized it as young adult. I hadn’t even thought about it. I didn’t even know what young adult literature was. I didn’t grow up reading it. But with a little perspective and a little distance from that work now, I look back and think, “Of course it was categorized as young adult because I was a young adult.” My natural tone skewed younger and what I was talking about skewed younger because I was younger. I sort of stumbled into the category and then decided to stay.

What books did you read as a kid?

I didn’t read any books until I was 17, almost 18. It just wasn’t my jam. If I had all the literature that we have today, I might have been better off. But at the time it just felt like, if you were a black kid, you were reading about the 1960s and 1970s. And you were reading about civil rights-unless you had [books by] Walter Dean Myers, but you had to have access to those books. And even Walter’s sweet spot was a little bit older than where I was in terms of the time and the era that he was covering. A lot of his work covers the ’70s and the ’80s. You know what I mean? I’m growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, and I’m looking for contemporary work. It just wasn’t a whole lot of it that I could get my hands on. And then after a while, you stop looking for it because you’re disinterested and uninterested. So it happened a lot later for me.

Can you share any reactions that you’ve received from kids about your work?

I mean, it’s interesting, right? I think, you know, there’s the hundreds of thousands of people who are upset about the end of The Long Way Down. I get asked about that the most probably when I see people. It’s always like, “What happened at the end of The Long Way Down?” Or more importantly, a lot of people, like teachers and parents, will tell me that it’s the first book their child has read or the first book that their child has finished.

I remember the responses to Ghost from young people who have experienced extraordinary trauma but haven’t let that stop them from being great, from being triumphant, from being happy. I’ve gotten a lot of comments that that book resonates with them-the complex decision-making that some young people have to make; the decisions that young people have to make when their backs are against the wall or when they feel like they’re doing the right thing even if the right thing breaks certain rules.

A lot of my stories put young people in situations where they’re forced to-or when they feel pressure to-make a decision that they deem to be right, even though it puts them in precarious situations, because that’s the life of my friends and family growing up. We didn’t always make the best decisions, but we thought we were making the right decisions. I want to show that. There are a lot of young people with their backs against the wall who are doing the best they can. They get chastised and disciplined and called all sorts of names, but the truth is, kids are doing the best they can, most of the time, with very little resources and sometimes very little support.

I’ve heard lots of beautiful things about For Every One. That book is a book that people revisit. That book is probably read the most, I think, by people who own it. I think they revisit it the most. And I see the quotes from that book all over the internet and on t-shirts and mugs, which is cool.

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You-a lot of young people reach out to let me know how upset they are because they feel like this information had been kept from them and how empowered they feel now that they have it. Now they have the language to talk about some of the complicated racial stuff in our country and the ideas around race in our country.

Two of your books-Miles Morales Spider-Man and Miles Morales Suspended-are set within the Marvel universe. What was that process like, working with characters and a world that has an established fan base, there’s canon involved, etc.? How did you approach that? Do you see a throughline between your work and the Marvel world?

I definitely see a throughline; I mean, my work is my work, right? When I take on the Marvel stuff, it’s still mine, right? And in that moment, it has to be. I have to look at it as if it’s my work, because my name is on it. I want it to read like any other Jason Reynolds novel.

That said, it obviously comes with different parameters. I find it interesting and challenging and cool to push myself creatively, but there’s a lot of things I can’t do because I don’t own this property. I have limitations and boundaries that I don’t ever have in my work, and I like to be sort of creatively free. I like to play around with whatever I want to play around with within the confines of my books. But when you’re dealing with intellectual property that you don’t own; when you’re dealing with something canon like Spider-Man-it has a different level of pressure because you want to make something that feels new and fresh, but also honors the legacy of the character.

Was this a new world for you? Were you a comic book reader as a kid or are you now?

No, not so much, but my siblings were comic book people. My older brother was a comic book nerd; he loves all that stuff. When I took on Miles Morales, he wasn’t famous yet. Not a lot of people knew who he was. There wasn’t a whole lot of information about him. He wasn’t a household name. I remember distinctly walking into schools and people being confused when I said I was writing a Miles Morales story. For me, I didn’t know a lot about him because there wasn’t a lot to know. And that was good for me as somebody who wasn’t a comic book person because I got to be a part of the building out of his character-who he is, how he acts, who his family is-and that’s cool.

You’ve had several of your works banned and challenged. How does that feel?

There’s anger, there’s frustration, there’s confusion. I find it to be pretty painful. It takes the wind out of me a lot of the times, because it offends me. When people are banning my books, what they’re really saying, at least implicitly, is that I’m doing something to harm children, that I’ve written something harmful. And I would never do such a thing. I’ve dedicated my life to edifying young people and to loving them and to doing my best to present work that helps them feel cared for. I would never make anything that I thought was harmful or produce anything that I thought was harmful.

That’s my biggest issue; that’s what it feels like. And I know it’s not about that; I know that a lot of it is just political nonsense. But that’s what my human emotions are. I’m frustrated and flabbergasted that someone would think that I would make anything that could put some young person-even their emotional state-in jeopardy. It’s never my intention.

Why is there an increase in book challenges at this moment in history? What do you think people are afraid of?

I think that people are afraid to communicate. I think we’re communicating worse and worse and less and less with each passing year. I’d like to believe that young people are getting better at it. I really think we don’t even know how to communicate anymore, especially with our young people. I think they know how to communicate with each other. But instead of learning and leaning into difficult conversations about an ever-changing world, we’d rather just gnash at the gate, right? It’s easier for us to tear things down or wall things off. Let’s put all the kids behind a stone wall so that they don’t see the world they already know exists. It’s a futile and silly thing to try and do.

I think what writers are doing is creating safe places for young people to explore a world that could very well be glorious and magnificent and might also have moments of danger without them having to actually live in danger. This is sort of a soft place to land in the midst of a complicated and sometimes slippery place.

I feel like so many adults don’t have the language and vocabulary, the definitions, or the lexicon to explore these new ideas and the new ways that we talk about these ideas, so the easiest thing to do is to shut it all down and to turn them into these monstrous avatars. When really they’re just simple conversations about race, sex and whatever else might be going on in the world that young people already know. Like they have phones in their hands, you know what I mean?

There’s this strange sort of way that people look at their children as like cherubic creatures, when the truth is that your child is a human being living a real experience, a life, a human experience in a real world and they may not know everything. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with parents saying that my child isn’t ready for this topic. That’s totally fine, I get that, but to say that no child deserves to read certain things is just ridiculous and unfair. How can you parent everybody’s kids? That’s not your job either, you know? We all have different experiences. There’s some 13-year-old who has never left his porch, and that kid might be terrified of a book like Long Way Down. And then there’s the 13-year-old who’s never had a porch. And to them, Long Way Down is very normal and very familiar.

What can we as librarians, parents, book lovers, and writers do to help combat the rise in book challenges and bans?

I’m never going to tell librarians what they can do because they’ve already done it all. They continue to do it. Librarians know exactly what the call is, and they’ve been fighting this for a long time. This isn’t the first time, but I think it may feel exacerbated at the moment and it might feel like it’s metastasizing differently. Librarians know what’s at stake. I’m careful because every librarian lives in a different place with different politics, different social stuff going on, different community problems, so I’m careful as we give too much advice as to what they should do besides what they’ve already been doing which is fighting to make sure those books stay on the shelves; making sure they’re talking to local politicians; building coalitions with other librarians.

I’ve had friends in certain libraries who’ve put their jobs on the line, and I’m careful about telling librarians to do that because we’ve all got to live and eat and take care of our children, you know. So instead of offering advice, I’d rather just offer my gratitude. I think we’re not doing enough of that. We talk about banning a lot, but we often don’t put our energy toward the people on the frontlines, risking their jobs and-in certain situations-their lives every day fighting for information to live. It isn’t [about] forcing it into any child’s hand, it isn’t [about] forcing it down any parents’ throat, it’s saying that these books deserve to exist and deserve to live on this shelf, and I have to allow for whoever wants to check it out, check it out.

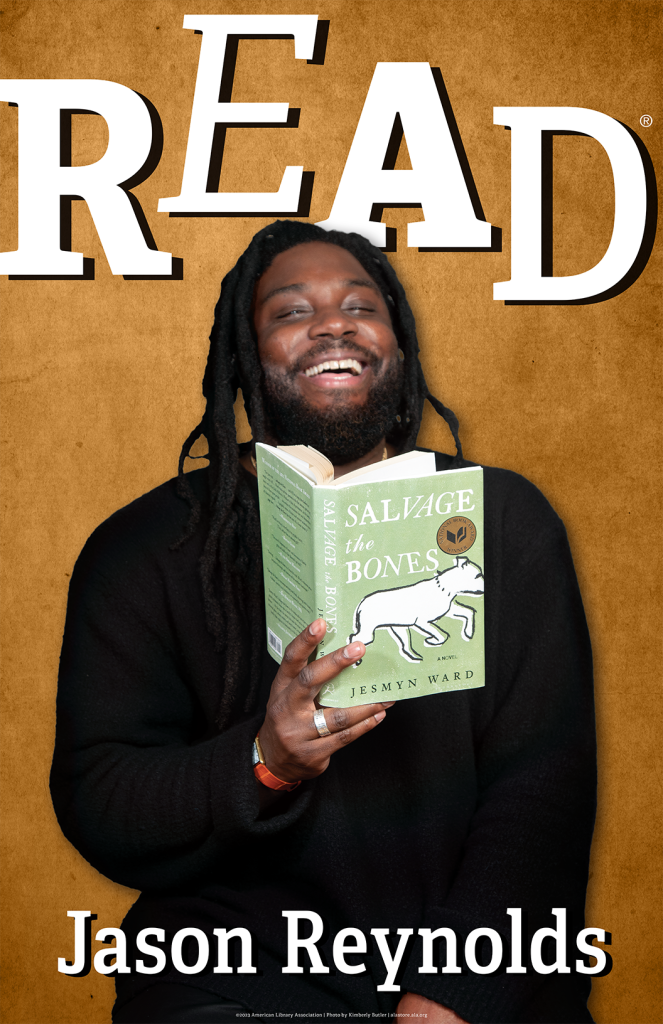

In your new ALA Celebrity READ poster, you’re holding Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward. Why did you choose this book?

In your new ALA Celebrity READ poster, you’re holding Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward. Why did you choose this book?

Because I think it’s probably, at least to me, one of the best books of the 21st century. I think that she’s the best writer of the 21st century. It’s a subjective statement, and yet in my mind, it feels objective. I think she’s that good; she’s that talented; and she’s that dialed into equal parts storytelling and language. That book-it shook me. I read it a long time ago now, and I’ve read it many, many times since. The way that I feel-and the way that many in the generation before me felt-about Beloved or Song of Solomon, I feel about Salvage the Bones. If there is an heir to Toni Morrison, it can only be her.

Can you share a story, a special moment, or an anecdote about libraries from your life, past or present?

In the past, I didn’t spend much time in libraries, because, back then for me, libraries felt like places where you had to be quiet, and I didn’t want to be quiet. They also didn’t necessarily feel like they feel now. Now libraries are places for everybody, not just the bookworms, not just the students, the scholars, or people coming in to find information. Libraries are places that are safe and accepting of the community despite what you come into the library to do. They feel more like community centers, and they feel sacred, as sort of worship centers to me. Libraries feel like a little bit of both of those things, where they could be a rec center or they could be a church. I think it’s special that the library holds both of those energies in one building, and I like that.

Now today, one interesting experience I remember? Gosh, I’ve had many, many, many nowadays, but I remember going to Ferguson (Mo.) Public Library in 2015, a year after Michael Brown was killed. Ferguson’s Black Lives Matter movement had just gotten started, and I went out there. I was touring for the book All American Boys, and it was an incredible experience to be in that library. That library, a little teeny place, they had won the Library of the Year award, and to hear about how in the midst of the uprising, the only institution that never closed was that library. The library was open all night, every day, housing people, allowing people to come and wash their eyes out, allowing people to come and take breathers and triage. That’s an incredible thing to think about. This is a space full of books and full of information and full of all of these things, but in that particular moment, it needed to be more and it became more. There’s something about that, metaphorically and literally, that I value and that I’ll never forget.

One last question and it’s a two-parter: What are you reading and what are you listening to right now?

I’m reading James McBride’s new novel, The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store. It’s super cool. It’s interesting. He has such a catalytic way of writing. His writing is sort of rhythmic. He’s a musician, so it’s very rhythmic and it’s sort of driving. It pulses in an interesting way-all of his writing does. I’m loving that.

What am I listening to these days? It’s weird, man; I listen to so much old hip hop, early Jay-Z stuff and anything like that. I love all the old stuff. But I’m also listening to a lot of amapiano, which is like South African sort of house music that I love. It’s probably my favorite sort of sound right now. I put it on any time of day. The tempo is right in the pocket, so in the morning it feels sort of soothing, like a nice welcome to the day; in the middle of the day, it feels sort of energetic; and at night it feels perfect for the evening with a glass of wine. But it’s all the same music, and I don’t know-it’s like they got like a secret sauce. You can put it on at any time, in any environment. You can drive to it; you can put it on and listen to it in a lounging sort of situation; you can play it at a party. It’s amazing, and it works for everything.

Photo: Adedayo “Dayo” Kosoko