The pandemic continues to fuel increased demand from library users for digital content like ebooks, digital magazines, and more. According to OverDrive, a leading provider of digital library content, in 2020, readers worldwide borrowed more than 430 million ebooks, audiobooks, and digital magazines, an increase of 33% compared with 2019 figures.

While patrons continue to discover and rely on digital content, libraries are engaged in a behind-the-scenes fight for fair pricing, multiple licensing models, and full access to digital content from publishers.

A recent position paper from the American Library Association, “The Need for Change: A Position Paper on E-Lending by the ALA Joint Digital Content Working Group (PDF),” calls for improved access, licensing models, pricing to serve readers and users of public, academic, and K-12 school libraries. The paper notes current and long-standing challenges in digital content lending and the issues that complicate acquisition of, user access to, and preservation of digital information.

We recently caught up with Michael Blackwell, Director, St. Mary’s County Library in Maryland and member of the ALA Joint Digital Content Working Group, to learn more about this hidden struggle:

What should library users know about how their libraries buy and share digital content like books, magazines, and films?

The most important thing to know is that libraries do not own most or nearly any of the digital content. Instead, we license it. Unlike with a print book, which we buy, own, and circulate, digital content circulation is still owned the publishers, who can set limits on the length of time we have the rights to share it or even say we cannot even have a license at all.

What are the challenges associated with the current model?

The challenges are many. Some of the smaller and medium sized publishers have favorable terms for libraries, but all of the Big 5 publishers, who put out some 95 percent of the best- selling titles, have restrictive licenses for ebooks. The licenses expire after a certain time or number of circulations. We must constantly relicense, often at relatively high prices.

With our ability to share the content only for one or two years, and at a price as much as five or six times what we pay for a print book, works by new authors or older titles that may not circulate heavily become a gamble to license. Will we get a reasonably return on our investment in them?

Some of the Big 5 still offer a perpetual license on audiobooks (which means we have no time limit on them) but at prices sometimes nearing $100, so that libraries are hard-pressed to get enough copies to meet demand. A pay-per-use option is offered, but it too can be cost-prohibitive. For example, President Obama’s most recent book A Promised Land costs libraries $9.50 per patron use -not a price libraries can sustain.

Still, this is better than the publishers who do not share content with libraries at all. The Digital Public Library of America announced a deal to share Amazon’s exclusive content on May 18 but Audible exclusives are still not available to libraries. Increasingly, media companies are moving to streaming video, and libraries cannot share this content digitally, having to rely on DVD versions, if those are even produced. In short, digital doesn’t offer us the “bang for the book” that we have in physical materials.

How does this impact readers?

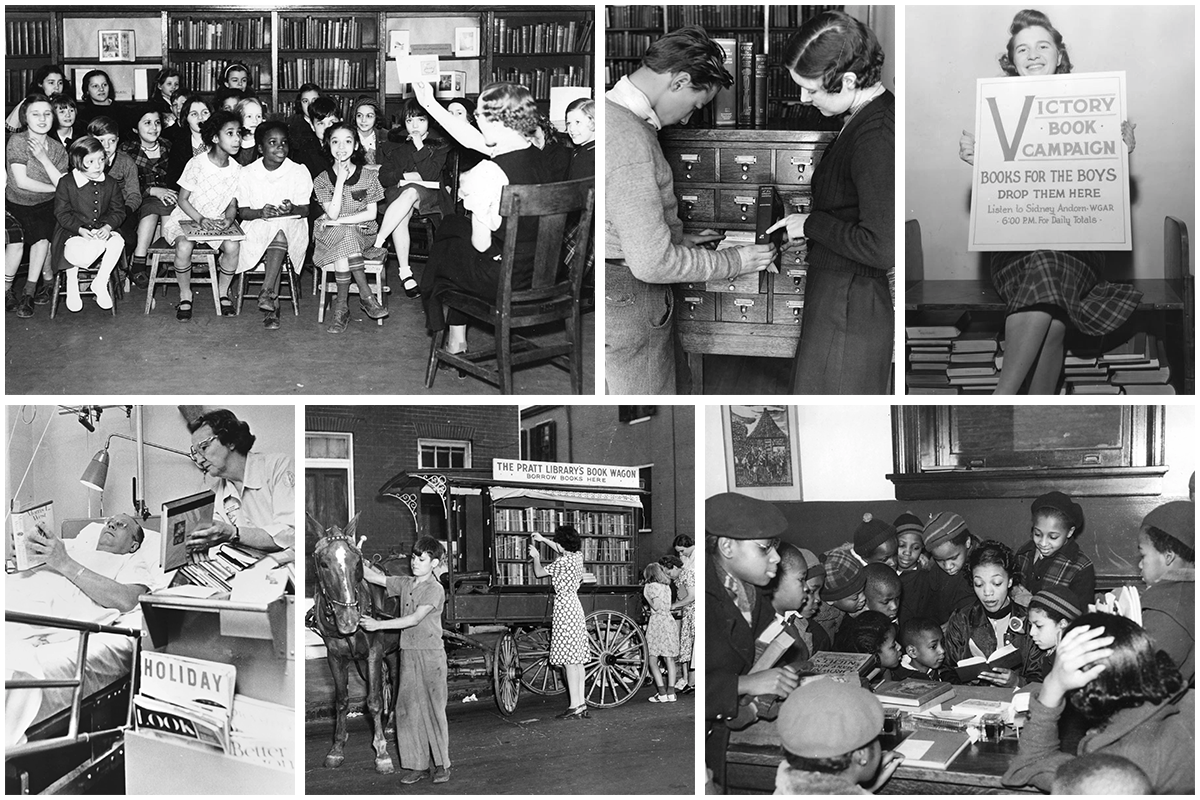

It is nearly impossible to build a collection as deep and rich as what we offer in print, even as demand surges for digital in libraries, especially in the wake of the COVID pandemic. Readers see less variety and have longer waits for the best-known content, especially as libraries are increasingly stretched by having to meet demand for digital while still providing print without notable increases in funding.

We also struggle to provide content from some of the smaller publishers that offer better deals because of the high cost of other digital content. In the long run, we may have to offer fewer of the most popular titles.

What are some examples of content readers cannot access through their libraries because of the lending models?

Titles can be inaccessible in two ways. Some content is simply not available digitally, at least in some formats. For example, Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime is available in libraries in ebook but not digital audiobook. Some titles, even classics such as Charlotte’s Web, are not available to libraries in any digital format. But titles can also be inaccessible because we are simply not sure they will get enough use to warrant licensing. For works of fiction by a new author or non-fiction work on an interesting subject that is getting no media build-up from its publisher, ebooks may not make sense. Print copies of those same title can be purchased inexpensively and promoted, but for a book that might only get six circulations at $60 for digital may mean collection developers won’t purchase it.

How can readers get involved in this issue?

Perhaps the best way is to become informed. Talk with your library, ask for their thoughts, and see if they have specific suggestions. Libraries sometimes join together on initiatives. For example, ALA launched the ebooksforall initiative when one publisher instituted particularly troublesome licensing, and we sought reader signatures on a petition. Maryland currently has a bill passed by the legislature and waiting its Governor’s signature that would require that publishers who license content to consumers also must license that content to libraries, ensuring that more titles would be available. Libraries in other states are considering action; if your state does, join libraries in advocating for such legislation.

Above all, use and support your library. We can’t do it without you! Become a library advocate today!