Felicia Cocotzin Ruiz is a storyteller and curandera who presents frequently around the country on traditional healing practices, culinary medicine, folk herbalism, and Native American food sovereignty. Her award-winning book, “Earth Medicines: Ancestral Wisdom, Healing Recipes, and Wellness Rituals from a Curandera,” has received praise from industry leaders including Padma Lakshmi, Dana Cowin, and Darin Olien. Her work has also been featured in Spirituality & Health, Forbes, Bon Appétit, and other outlets.

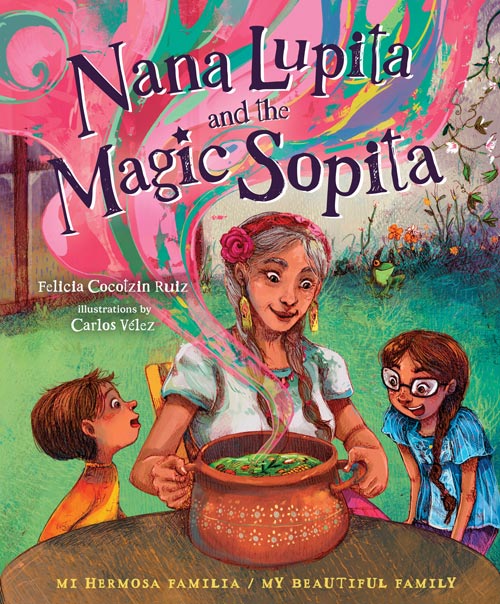

Ruiz’s first picture book for kids, “Nana Lupita and the Magic Sopita,” illustrated by Carlos Vélez and published in July 2024, is an enchanting story that features the mystery of a grandmother’s secret sopita recipe, a seek-and-find of healing plants, and bilingual words for young readers that includes the recipe for Nana’s magic soup. The follow-up, “Tia Sofia and the Giant Tortilla,” was released in August 2025.

We sat down with Ruiz in her hometown of Phoenix, Arizona, to discuss “Nana Lupita and the Magic Sopita,” her work as a curandera, book bans, and her love of libraries.

“Nana Lupita and the Magic Sopita” tells a colorful story about a young brother and sister on a hunt to find out the ingredients in their Nana’s medicinal soup. What inspired you to tell this story?

Partly my culture. We’re very much into caldos, which means “soup.” Anytime anyone’s sick, feeling unwell with a cold, going through postpartum times, any type of illness, we go to soup. That was a big part of not only my upbringing, but it’s also how I operate in everyday life. For me, writing a whole book around soup seemed really special.

You’ve written several books, but this is your first for young readers. What led you to write for this age group?

In second grade, I won a young authors award. Actually, I think I got second place. I knew then I was going to be an author someday!

Being a brown kid in the Phoenix area, I did not see books with characters that looked like me. After I got older and finished my first book, which was a lifestyle book, I put in my editor’s mind that I had always wanted to write a children’s series. And that’s how I got this book deal.

You’re a curandera, a traditional healer. What is that exactly? Is it something that runs in your family?

Yes. My great-grandmother was a curandera. For people that don’t know that word, I usually tell them to imagine a traditional healer, a medicine woman, a wise woman. And there’s also curanderos (male healers). In my own family, they were all women. People who were midwives; people who worked with herbs; people who worked with more spiritual things. That was my great-grandmother. She was very well known in Old Town Albuquerque, catching babies, as we say, and helping people with different herbs. This is something that is very embedded in my lineage.

Your book is full of history, from the folk remedies that the grandmother makes to the uses of the herbs and so much more. Was that an important part of writing the book for you, to impart that history to young readers?

Yes. I wrote it wanting children to be enamored with it. However, I knew that probably a guardian, parent, or librarian would be reading it to them, so I wanted to spark interest in them too. I wanted them to be curious about what curanderismo [traditional folk healing] is. We’ve just kind of come out of the closet in the last 20 years or so [in terms of] being able to speak freely about our way of healing. A lot of people don’t know about this practice.

You’ve been nicknamed the “kitchen curandera.” And you’ve included a recipe for the magic sopita in the book, along with terms and definitions for the herbs featured. It’s a fascinating book for readers of all ages. Is that your grandmother’s recipe, by chance?

No, we didn’t grow up eating that soup. Traditional sopita is usually made with something called fideo which is like a very thin, spaghetti-like pasta. However, I really wanted to focus on the broth and allow people to use pasta. They could use corn; they could use whatever they wanted in the soup. I made the base as slimy as possible, because the children in the book are assuming their Nana is making soup from frogs. So I wanted the soup’s base to be really slimy. There’s a lot of tomatillos in there, and those type of ingredients that tend to make that slimy Jello [consistency].

A lot of your work revolves around Indigenous food, and you’re an advocate for Indigenous foods. What are some of these and how can we add them to our diets or use them?

That’s actually a big branch of what I do, speaking on Indigenous foods. As an Indigenous foods activist, I tell people to start by using what is growing naturally in their area. We’re such a diverse country with all these different ecosystems. For me to tell someone to go eat prickly pear cactus or mesquite pods, that might not make sense for someone who lives in Vermont. So I tell people to really look at what’s in their backyard growing wild.

Carlos Vélez’s illustrations are lovely. What was your working relationship like with Carlos? Were you involved in the look of the book, or did you simply give him the copy and say, “Do your magic?”

When I finished writing the book’s proposal, I was given the choice of who I wanted to work with [as an illustrator]. I loved Carlos’ work, so we signed him on. Months later, when I was in Mexico City for work, I got to meet him, and we hit it off. He loved the story. He said it reminded him of his own grandmother’s home. He was able to capture it all, even without my notes—and I had extensive notes of what I wanted to be in Nana’s kitchen, what I wanted to be on the walls.

One thing I really appreciate about the book is that it’s a fun read for readers of all ages. We’re encouraged to be attentive while reading and find and identifythe herbs illustrated on each page. Was that something you and Carlos worked on together? Or was that in your initial proposal for the book?

As a child, I would go wildcrafting with my great-grandmother. I wanted to bring that energy to the book, of going out to seek and find plants because that’s how you learn. You identify a plant, then you go out and look for it in the land.

The American Library Association has been tracking and fighting book bans and censorship for decades. Many book challenges that we encounter involve the silencing of stories by and about marginalized communities and BIPOC and LGBTQ+ people. As an Indigenous person and creator, what are your thoughts on this unfortunate situation?

I am very invested in helping our community have access to books that are on banned lists. It’s important to me. Many of the books that I did have a privilege to read have now been banned many times. I feel like “Nana Lupita and the Magic Sopita” could be banned just because it’s semi-bilingual and about empowering yourself with herbs and the old ways.

I feel very strongly that, as a collective, we’re moving through something very difficult right now. I hope that the light at the end of the tunnel means that the books will be available for everyone.

Do you have any cherished memories of the library that you’d like to share?

I love the library. When I was a little kid, I won a reading contest at my local library, I think I was in the second grade. You had to read so many books, and they would put a little graph together, and whoever read the most won a little book bag—or maybe it was just a bookmark. I won the prize! For me, that was a very solidifying relationship with my library.

Now, well into my 50s, I still go to different libraries but for different reasons. When I was writing “Nana Lupita and the Magic Sopita,” I would go and just watch children that were doing storytime or playing in different areas of the library to get information on how kids play and what they say to one another. I was using it as a form of research. Now that I now have two books out, though, I must be honest and say that I like to go to the library to find my own book. It feels absolutely full circle.

How you can support libraries

With library funding being gutted and censorship on the rise, supporting libraries is more critical than ever. If you’re looking for a way to help, we urge you to become a Supporter of the American Library Association by donating.

At the American Library Association, we are here to protect libraries — today and for generations to come. What does your donation do? It helps a neighbor gain skills to start a business. It helps a child discover themselves through books and programs. And it helps keep libraries strong, open, and free for everyone.

Become a Supporter

Subscribe to the I Love Libraries newsletter! You’ll get news from the library world, advocacy updates, author interviews, book lists, and more delivered to your inbox every month.